This is a series exploring the Theory of Constraints and related ideas. I don’t know how long it will go on, or where we’ll end up, but I will limit myself to a 5-minute read per post. TOC starts with basic concepts but builds to quite profound ones, and I want to share what I am discovering with you busy movers and shakers.

The Theory of Constraints is deceptively simple. It starts out proposing a series of “obvious” statements. Common sense really. And then before you know it, you find yourself questioning the fundamental tenets of modern business and society.

Eliyahu Goldratt laid out the theory in his 1984 best-selling book The Goal. It was an unusual book for its time — a “business novel” — telling the story of a factory manager in the post-industrial Midwest struggling with his plant. The problems this manager faces are universal, of course, and not only for manufacturing. For 30 years now, readers have recognized their own situation in this fictional story. This flash of recognition is the hook drawing you deeper into the TOC world.

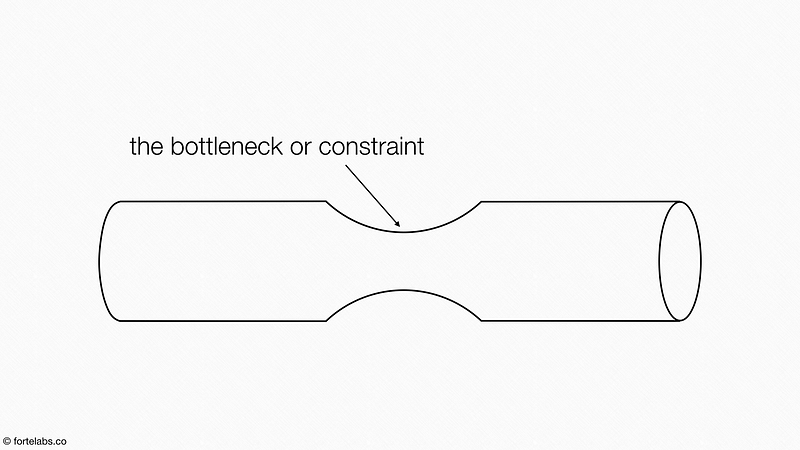

The first statement that TOC makes is that every system has one bottleneck tighter than all the others, in the same way a chain has only one weakest link.

For some systems you can see it plainly: the cars always slowing to a stop in that same section of freeway; that doorway in the office where everyone’s paths seem to converge; that one curve of your plumbing that you can’t seem to keep unclogged.

For other types of systems, it’s less obvious. It helps to broaden the concept from bottlenecks, which describe material flows, to constraints of any kind.

What is the constraint preventing a coffee shop from serving more customers? It’s not the size of the doorway. It could be the rate of cappuccino preparation, the speed of credit card approval, or the number of people wanting coffee in that place and time for that price. It’s not always easy to tell where the constraint is actually. But we know it’s there, or else the shop could serve an infinite number of customers at infinite speed.

What is the constraint keeping the human body, let’s take Usain Bolt’s for example, from running faster? It could be his body’s ability to metabolize glucose or oxygenate his muscles; or his shoe’s grip on the track surface; or a limiting belief somewhere in the depths of his mind.

Clearly, it gets even harder to find the constraint once we enter the world of the abstract, the psychological, and the immaterial. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

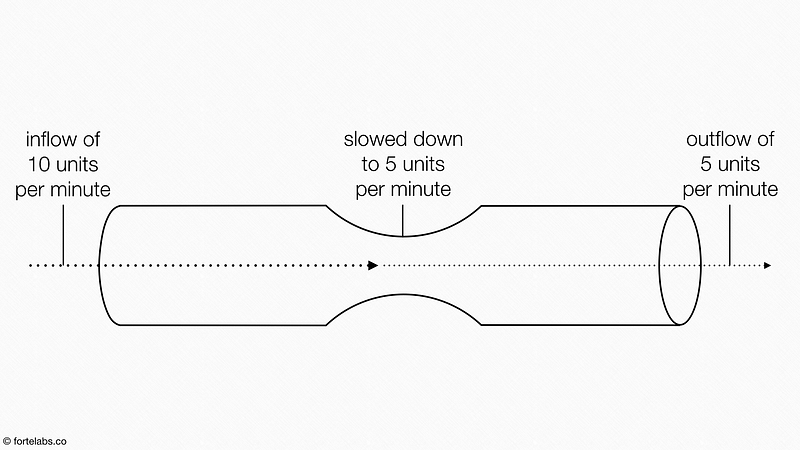

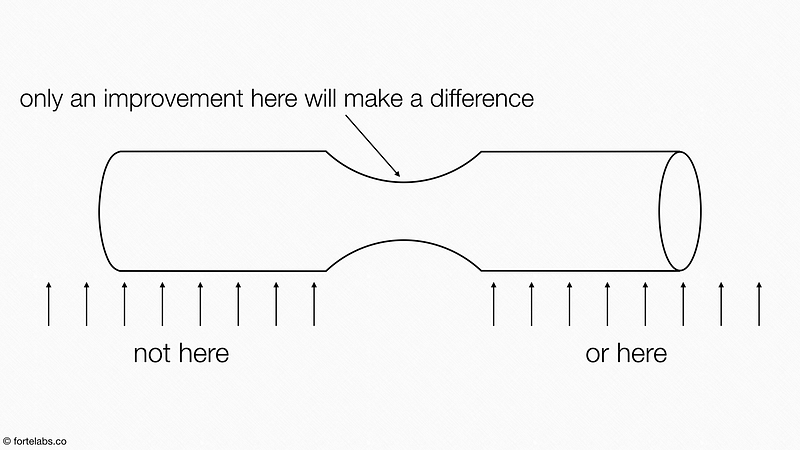

The second statement is that the performance of the system as a whole is limited by the output of the tightest bottleneck or most limiting constraint.

In other words, if the water in a pipe is slowed down to a trickle by a narrow section, the outflow at the end of the pipe will be no more than a trickle. This one is harder to see intuitively, because it is obscured by the messiness of the systems we typically interact with.

That coffee shop cannot serve customers one iota faster than the speed of its cash register (if that is the constraint). Usain Bolt cannot shave one microsecond off his time without increasing his proportion of fast twitch muscle fibers (if that’s his most limiting constraint).

The third statement follows from the first two , but is the hardest to swallow. It is the red pill of TOC: if the first and second assumptions hold, then the only way to improve the overall performance of the system is to improve the output at the bottleneck (or more broadly, the performance of the constraint).

Using the coffee shop example, if the most limiting constraint is the cash register, literally nothing else will make a difference to the bottom line except an improvement in cash register speed. Not better customer service, not higher quality food, not better interior decoration, not faster WiFi or cleaner bathrooms or stronger coffee or any one of the million other ideas we could come up with in a freewheeling Design Thinking workshop. Any improvement not at the constraint is an illusion, for the same reason there’s no way to strengthen a chain without strengthening its weakest link.

Now think about how a typical company operates. The CEO announces it’s time for the company to improve. That command gets translated down the ranks, each manager impressing upon his team the importance of their individual efforts. Each person hears what they want to hear: the accountants understand that they must improve the usefulness of the books they keep (with each person interpreting “usefulness” differently). The software devs nod in agreement that better code is crucial (with each person interpreting “better” differently). The marketing people agree that more creative promotions are the only solution (with no one bothering to define “creativity”).

Each person marches off on their personal mission, nose to the grindstone, performance bonuses on the horizon, without realizing that their collective efforts imply a management philosophy:

Local improvements everywhere automatically translate into the global improvement of the organization.

John Maynard Keynes once said, “Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influence, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist.”

What if this implied management philosophy was dead wrong? What if, by believing that we can improve a system as a whole by individually improving each part, we are living and working according to an economic paradigm that has been defunct for decades?

That is what the Theory of Constraints proposes, and the problem it seeks to resolve.